Athenaeum Club timeline

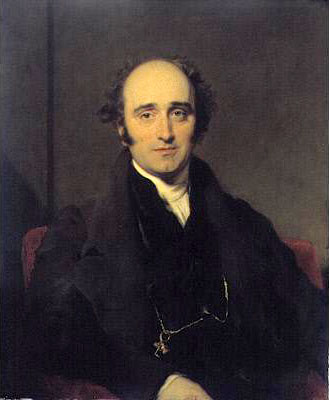

The Athenaeum Club was founded in 1824 by John Wilson Croker MP, First Secretary to the Admiralty, a leading figure in literary circles and a moving spirit at the Union Club. The Club was intended to serve as a meeting place for artists, writers, and scientists, along with cabinet ministers, bishops, and judges, where relationships could be fostered and ideas exchanged beyond the boundaries of the learned societies and other national and local organisations of the day, to which many members also belonged.

- 1823 12 March: From John Wilson Croker, First Secretary to the Admiralty, to Sir Humphry Davy, President of the Royal Society: I will take this opportunity of repeating the proposition I have before made to you about a Club for literary and scientific men, and followers of the fine arts.

- 1824 16 February: A planning committee meets in the apartments of the Royal Society, Somerset House, on what was truly the birthday of the Club, which was as yet unnamed.

- 1824 31 May: A temporary clubhouse at 12 Waterloo Place is opened to members.

- 1824 22 June: The first 506 members are invited to present copies of their published works for the purpose of forming a Library for the use of the Club.

- 1825 January: By now the Club already boasts 990 ‘original’ members.

- 1830 February: The Club moves to Decimus Burton’s Grecian clubhouse on the corner of Pall Mall and Waterloo Place (where is remains today), and it opens to great acclaim. The Committee may invite nine particularly eminent ‘Rule II’ members to join each year to bypass a long waiting list.

- 1831: The Club Archive shows that a ‘Joint with Bread & Table Beer’ can be obtained for one shilling (5p), and ‘Two Eggs’ for sixpence (2½p).

- 1838 June: The Club’s Committee authorises an expansion of the number of Club members to help finance running costs and improvements. The extra members (dubbed the ‘Forty Thieves’) include Charles Darwin and the young Charles Dickens.

- 1840s: The popularity of the Club means that the waiting list for membership continues to grow, peaking at 1,500 members held in a 16-year queue.

- 1857 10 August: The Club’s founder, John Wilson Croker, dies, aged 76, having seen his Club become one of the landmarks of London.

Members would have baulked at the idea of advertising for new recruits. But they didn’t need to, as it was perceived as an honour to be nominated for membership. Whilst many of the leading figures of literature, science, and politics in the later nineteenth century might be seen walking into the Club, others who played important but quieter roles on the national and global stage were eager to join and to exchange views with the opinion-formers of the day.

- 1863: The Club Archive shows members engaged in activities outside the range of the work for which they are best remembered. Scientist Thomas Huxley, for example, joined other members of the X-Club campaign to “professionalise” science for Bishop Colenso of Natal to be granted honorary membership of the Club. Most Anglican bishops are Club members and most heartily disapprove.

- 1866 24 July: The windows of the Morning Room on Pall Mall are smashed by the mob after the failure of one of the Reform Bills.

- 1869-80: Records show that of the 62 members of the Metaphysical Society (a famous debating society founded in 1869), 44 are Club members.

- 1873 May: John Stuart Mill, a regular member (and the son of original member James Mill) who joined before he was prominent as a leading thinker of the late Victorian age, dies. This sparks a row in the Club over his radical views on birth control.

- 1887: Philosopher and proponent of ‘social Darwinism’ Herbert Spencer protests against ‘strangers’ being permitted to join private dinners in the Club; in the same year a new Executive Committee chaired by Sir Frederick Abel is established to streamline the management of the Club.

- 1891-2: As tastes change and older buildings need a face-lift, Sir Edwin Poynter and Sir Lawrence Alma Tadema are invited to remodel the interior decoration of the Club.

- 1893 11 March: The iconic sketch Ballot Day 1892, in which many Club members of the day can be identified discussing and casting their ballot, is drawn by J. Walter Wilson and published in ever-popular Illustrated London News.

- 1899: Redesign does not always meet with approval: Thomas Calcutt’s undistinguished extra storey added to the Clubhouse is mocked as a ‘birdcage’.

As the Club moved into the 20th century it started to be more aware of its own history and to recognise that it needed to move with the times to satisfy the demands of a membership which had emerged from the Victorian era and was experiencing the new reality of life after the Great War, mass production, mass communication, and the emergence of new generations of writers, scientists, and thinkers.

- 1902 4 July: The Club is delighted to discover that nine of its members are included amongst the 12 initial members of King Edward VII’s new Order of Merit. Their achievement is celebrated at the Club’s first banquet, where Prime Minister and Club Member Arthur Balfour proposes their health.

- 1904: Club Members Lord Rayleigh (Physics) and Sir William Ramsay (Chemistry) are each awarded a Nobel prize, the first people from the United Kingdom to gain such an honour, and the first of over 50 Club awardees over the years.

- c1912: Arthur Benson acts as an interpreter for Thomas Hardy and Henry James, both of whom are hard of hearing.

- 1914 1 November: Two members of the Club’s staff, Lance Corporal Alfred Brown, junior clerk, and Private George Weekes, sculleryman, are killed in action at Messines.

- 1914 19 November: Much-loved British military commander Earl ‘Bobs’ Roberts is buried at St Paul’s Cathedral, at the age of 82.

- 1916-17: The Revd. Carew Hervey St John Milmay exchanges 42 letters with the club’s Executive Committee regarding his own complaints and those made against him.

- 1924 16 February: The Club holds its ‘Foundation Day’ centenary dinner.

- 1924 March: Newly-elected Ramsay MacDonald, the first Labour Prime Minister, unwittingly breaks the complex rules on ‘strangers’ in the clubhouse, and is required to cut short his visit to the clubhouse.

- 1926 22 November: The Club launches a new initiative with the first ‘Talk Dinner’, on ‘Coal’.

- 1940 14 October: The clubhouse is ‘rocked’ when Carlton Club takes a direct hit from a German bomb.

- 1940-5: Exiled foreign leaders and their ministers become honorary members. Prominent scientists such as Sir Henry Tizard, Lord Blackett and others meet in clubhouse to discuss the emerging technology of radar, etc.

- 1974: Club Chairman Sir Percy Faulkner, Controller of Her Majesty’s Stationery Office and Queen’s Printer of Acts of Parliament, declares the Athenaeum to be more than just another London club.

- 1985: Members include four Presidents of the Royal Society, two of the Society of Antiquaries and six of the British Academy.

The 21st century sees further changes in the Club, as its membership becomes more diverse. But it is still based at Decimus Burton’s clubhouse on the corner of Pall Mall and Waterloo Place in London, and still fosters the same style of intellectual debate and exploration that its early members established.

- 2001 March: After three debates over 17 years, women members are admitted to the Club: the ‘First Ladies’.

- 2018: Jane Barker becomes first woman to be elected Club Chairman. The present full complement of members is 2,000.

- 2024 16 February: Bicentenary of the Athenaeum Club.